Anna M. Kotarba-Morley, Flinders University

Many think of globalisation as a modern and corporate phenomenon, and it has been readily linked to the spread of coronavirus.

But globalisation isn’t new. Archaeological research shows it began in antiquity.

A global economy, with luxury consumerism and global interconnectivity, linked Europe, Africa and Asia at least 5,000 years ago and was widespread 2,000 years ago.

Over the past decade, archaeological excavations of ancient ports of trade have revealed prosperous networks of maritime and terrestrial trade that flourished in the ancient world.

Recent discoveries challenge our understanding of global economies and international connectivity through studies of architecture, excavated trade goods, and “ecofacts”: organic evidence (such as seeds, pollen or various sediments) associated with human activity.

Commercial ports and hubs linked the Indus Valley civilisation in South Asia with those of ancient Dilmun (current-day Bahrain) – a southern gate to Mesopotamia – some 4,500 years ago.

The Roman and Han empires – and everyone in between – were directly connected through outposts across the Indian Ocean some 2,000 years ago, foreshadowing our globalised world.

Common goods and exotic luxuries

Berenike, a small Roman city of about 2,000 inhabitants on the southern Red Sea coast of Egypt, was one of the key international trading hubs. The site was operational for over 800 years from its foundation by the Pharaoh Ptolemy II to bring African war elephants to Egypt.

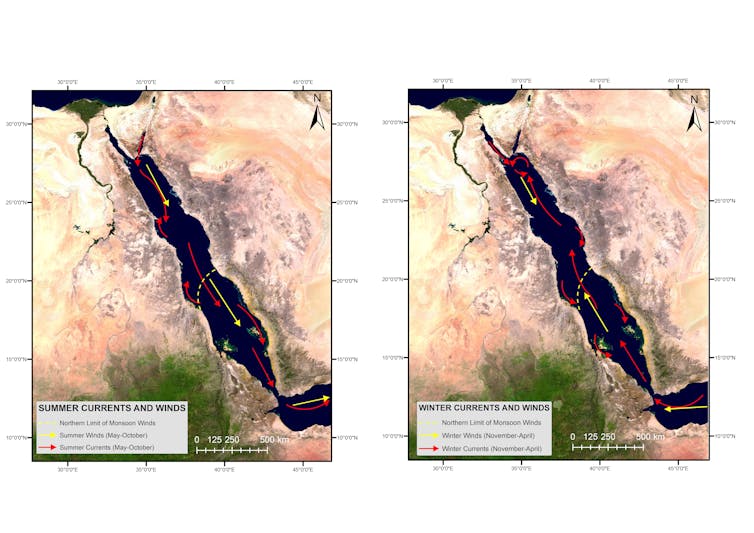

The city was one of the starting points of the Periplus Maris Erythraei (Circumnavigation of the Red Sea), an ancient merchant guidebook written in the first century CE. Located strategically at the northernmost reach of the monsoon winds, Berenike received goods from across the Indian Ocean to be packed on camel caravans and transported along desert routes to the Nile. At the Nile port of Coptos, goods were reloaded onto riverine ships travelling to Alexandria and then across the Mediterranean.

Excavations at Berenike have yielded organic remains, common trade goods and exotic luxuries. These attest to contacts as far north and west as Spain and Britain and as far south and east as southern Arabia, sub-Saharan Africa and Sri Lanka. Indirectly, these ports provided contact with Vietnam, Thailand and eastern Java.

It is believed Berenike fell into disuse around the sixth century CE due to the Plague of Justinian.

An interconnected world

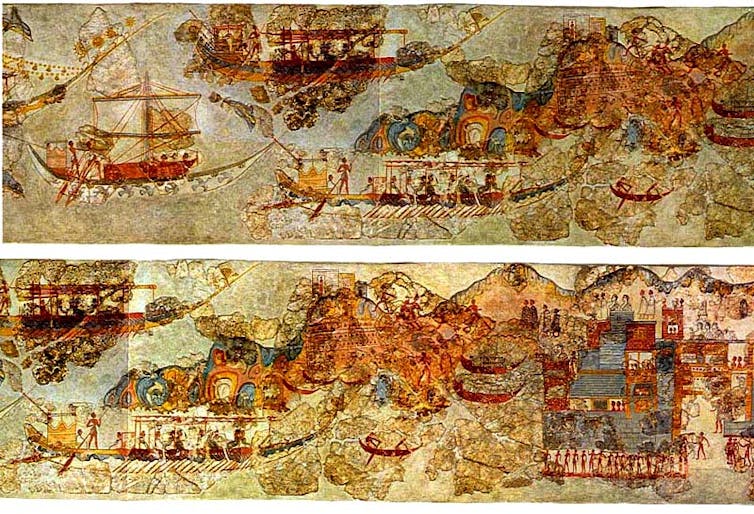

Humans have been involved in seafaring since the Stone Age. Over time, shipbuilding and navigation technologies improved. More than 2,000 years ago, Indian, Arab and Roman seafarers mastered the monsoon routes.

By understanding Red Sea wind patterns and Indian Ocean monsoons, the journey to South Asia could be made without reliance on time-consuming coastal hopping.

In the late 15th and early 16th centuries, explorers like Christopher Columbus, Vasco de Gama and Ferdinand Magellan set out on journeys with an almost single-minded purpose: to acquire exotic spices. This “Age of Exploration” came long after far-distance trade bridged continents.

In July 1497, de Gama left Lisbon, arriving in the Kenyan port of Malindi in April. There, he hired an Arab mathematician, Ahmed Ibn Magid, who flawlessly navigated the monsoon route to the Indian port of Kozhikode.

After circumnavigating Africa and 23 days of open sea voyage, da Gama and Ibn Magid arrived on the Malabar Coast in a journey of under a year.

Similar journeys would also have taken just under a year in Roman times: by sea from Rome to Alexandria, by river from Alexandria to Coptos, by caravan from Coptos to a Red Sea port, and across the sea to India. Dependent upon monsoon winds, Roman merchants could undertake this journey only once a year in each direction.

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, improvements in shipbuilding and the opening of the Suez Canal reduced the journey from England to India to between four and six months, running all year round in both directions. Nowadays the Suez Canal records upward of 20,000 passages a year.

Today, powerful modern cargo ships take 20 days on the same route. You can fly from London to Mumbai in nine hours.

The unprecedented rapid spread of COVID-19 is just one of the many legacies of the globalised ancient world.

Internationalised old world

With borders closing and travel restrictions remaining widespread, many are questioning “modern” globalisation, but far-distance trade and exchange networks have interconnected the world since the Bronze Age (3300-1200 BCE).

Ongoing archaeological investigations help shape important narratives relating to human mobility, placing modern debates about cross-cultural interchange, migrants-versus-expats narratives, global and local religions, forced and voluntary migration, as well as adaptation and assimilation patterns within a wider historical framework.

In the world of growing political division, it is important to remember the ancient world, with all of its shortcomings, was open, tolerant and multiracial. It was not that strikingly different to the world of today.

Anna M. Kotarba-Morley, Lecturer, Archaeology, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.