The origin of the human species remains one of the most fascinating and difficult topics of modern science.

One of the main reasons for this is a continuing lack of agreement about how we should define ourselves. In other words, what is it that makes us human (or, scientifically, Homo sapiens)?

The father of biological classification, 18th century Swede Carl Linnaeus, wrote in his Systema Naturae the words “nosce te ipsum”, or “know thy self”: a statement at once prescient and frustratingly uninformative.

More annoying, the issue of how we define “human” seems to get more complicated the more fossils we unearth.

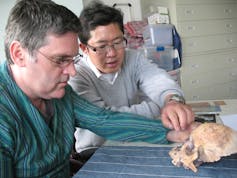

A new study published today by a team of Australian and Chinese scientists – led by my colleague Ji Xueping and I – opens a new chapter in the story of human evolution in East Asia.

Our team investigated the recent phases of our evolution in southwest China, including the origins of modern humans in the region. In our paper we describe and compare human fossils from two sites in the region: Maludong, near the city of Mengzi, Yunnan Province, and a cave almost 300km, away located near the village of Longlin in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region.

Our discoveries raise far more questions than they answer, adding to the complexity surrounding the origin and definition of modern humans.

Our research uncovered a new population of prehistoric humans whose skulls exhibit an unusual mosaic of primitive features, such as those seen in our ancestors hundreds of thousands of years ago. The skulls also exhibit some modern traits, similar to those seen in living people, as well as several unusual features.

Specifically, the “Red Deer Cave people” have:

- rounded skulls with prominent brow ridges

- short, very broad and flat faces, tucked under the front part of the brain

- broad noses

- jutting jaws that lack a human-like chin

- brains moderate in size with modern-looking frontal lobes, but primitively short parietal lobes, and

- large molar teeth.

This mosaic of skull features makes it difficult to decide whether the Red Deer Cave people should be classified as Homo sapiens or as some other species. Indeed we have refrained from classifying the fossils at this stage.

That said, we think the evidence is weighted towards the Red Deer Cave people representing a new evolutionary line. Why?

Well, first, their skulls are anatomically unique. They look very different to all modern humans, alive today, or alive at any time during the 150,000-year sequence of Homo sapiens fossils we have.

Second, the fact the Red Deer Cave people were around until almost 11,000 years ago – when very-modern-looking people lived immediately to the east and south – suggests the Red Deer Cave people must have remained isolated.

We might infer from this isolation that they either didn’t interbreed or did so in a limited way.

Another possibility is that the Red Deer Cave people represent a previously unknown modern human population that arrived early (roughly 60,000 years ago) from Africa and failed to contribute genetically to East Asians alive today.

Either of these proposals would make sense. After all, at between 14,500 and 11,500 years old, the Red Deer Cave people are the youngest population anywhere in the world whose anatomy doesn’t fit comfortably within the range seen in modern humans over past 150,000 years.

But while the evolutionary make-up of the Red Deer Cave people remains a mystery, there are some things we do know.

For a start, we know they lived in southwest China at the end of the Ice Age. They survived the final (and one of the worst) cold episodes, known as the Last Glacial Maximum, which ended roughly 20,000 years ago.

The period around 15,000 to 11,000 years ago, when Red Deer Cave people thrived in southwest China, is known as the Pleistocene-Holocene transition. This period saw a shift to climates and ecological communities much the same as we see today.

This period also saw the demise of the mega-fauna in most places, including a giant deer that was exploited by the Red Deer Cave people and recovered in large numbers from the Maludong site. It seems that the Red Deer Cave people hunted and cooked these large deer in their cave.

The Pleistocene-Holocene transition also saw a major shift in the behaviour of modern humans in southern China. It was at this time humans began to make pottery for food storage and to gather wild rice. These are the first steps towards full-blown farming.

The Red Deer Cave people were sharing the landscape with these early pre-farming communities, but we have no idea (yet) how they may have interacted or whether they competed for resources.

It’s even possible that the changes in economic behaviour of modern humans living nearby – associated with the beginnings of farming – may have pushed the Red Deer Cave people to the brink.

It’s interesting to note that it wasn’t just modern humans and the Red Deer Cave people living in East Asian at the time. There was also Homo floresiensis (or the “Hobbit”), which lived on the island of Flores in western Indonesia.

The existence of multiple populations – probably from different evolutionary lines – paints an amazing picture of diversity; one we had no clue about until the last decade.

It’s probably the tip of the iceberg of diversity and the opening of a new chapter in recent human evolution – the East Asian chapter.

The location of these fossils in East Asia only deepens the mystery surrounding human evolution in the region. Our discovery also underscores how little we know, even about a relatively recent period.

We can only assume the Red Deer Cave people evolved in the region, but we have little idea about their evolutionary history or relationships to other humans at this stage. The successful recovery of DNA from their bones would help us answer many questions about their ancestry.

We’ve had one unsuccessful attempt already, but we are doing more work involving three of the world’s major ancient DNA laboratories and cutting-edge techniques.

DNA might also provide us with the chance to classify the Red Deer Cave people with some kind of certainty.

Finally, DNA extraction might also help us narrow down that elusive list of Homo sapiens features; a list we’ve been trying to compile for more than two centuries.

Darren Curnoe, Human evolution specialist, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.