Amy Prendergast, The University of Melbourne

This article is part of our occasional long read series Zoom Out, where authors explore key ideas in science and technology in the broader context of society and humanity.

Watching the weather for today and tomorrow is relatively easy with apps and news programs – but knowing what the climate was like in the past is a little more difficult.

Archaeological evidence can show us how humans coped with long-gone seasonal and environmental changes. For me, it’s fascinating because it reveals what life was like back then. But it’s useful beyond that too. This body of data helps us understand and build resilience to climate change in the modern world.

Archaeological data is now of a standard where it can map past climate variability, offer context for human-induced climate change, and even improve future climate predictions.

Surviving all the seasons

As Earth takes its annual trip around the Sun, temperature, daylight hours and water availability vary through the seasons. These dictate natural cycles of animal breeding and migration, and plant fruiting and flowering. Such cycles control the availability of food, shelter, and raw material resources.

People living in cities might notice the changing seasons: autumn leaves turn a golden hue, and in summer fresh berries fill the supermarket shelves.

However, modern technology and global trade networks lessen the impact of the seasons on our daily lives. We can buy strawberries at any time of year (if we pay a premium). We can escape summer heatwaves by turning on air conditioners.

In most parts of Australia, our lives no longer depend on tracking the changes in plants and animals throughout the year. But in the past, if you weren’t in tune with seasonal patterns, you wouldn’t survive.

In my work I study how past people interacted with seasonal changes, using evidence from archaeological sites around the world.

Past and present seasonal patterns have changed due to climate change, causing cooler winters, warmer summers, or altered rainfall. Different seasons may occur earlier or later, last longer or be more extreme.

These changes have flow-on effects that can be detected in the archaeological record.

Life in ancient Libya

One archaeological site where seasonal changes have been well studied is the Haua Fteah cave in the Gebel Akhdar region of Libya.

The Haua Fteah covers the transitions from prehistoric hunter-gatherers (beginning around 150,000 years ago), and prehistoric farmers (beginning around 7,500 years ago), right the way through to more recent times.

We found the Haua Fteah experienced the most arid and highly seasonal conditions just after the last global ice age. This changed the plant and animal resources available in the local landscape over 17,000 to 15,000 years ago.

However, despite the climate and resource instability, human activity was the most intense during this period.

To investigate this, we compared climate records from the Gebel Akhdar and adjacent regions of North Africa.

It turns out that even though the Gebel Akhdar had an arid and highly seasonal climate, it was not as arid as surrounding regions at this time. Scientists believe that increasingly dry conditions elsewhere led to population increases at the Haua Fteah – people were simply seeking a less hostile place to live.

Additionally, use of shellfish as a food source changed from a predominantly winter-focused activity to a year-round activity during this period.

Year-round shellfish reliance was probably an adaptation to supplement the diet when other resources were less available. A mixture of climate and population pressures likely drove the restriction of resources and reliance on shellfish.

But beyond just knowing what people ate, and when, hiding in such shells (and other items) are clues about regional differences in seasonality.

Here’s how it works.

The remains of ancient meals

Archaeologists are essentially trash sifters. We use clues preserved in artefacts, plant and animal remains that people threw away or left behind to reconstruct the past.

Hard animal parts, including mollusc shells, teeth, fish ear bones (otoliths) and antlers, are routinely preserved in archaeological sites. These items accumulate from hunting, fishing, farming, and foraging activities.

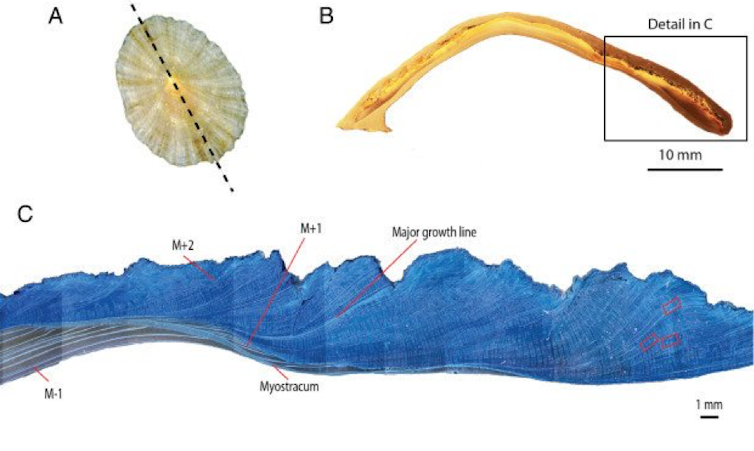

The growth of these animal parts over time forms periodic growth rings, or increments. Much like tree rings in dendrochronology, the structure and chemical composition of these increments is influenced by the environment. By analysing these increments, we can understand what the environmental conditions during the animal’s life may have been like.

Seasonal variations in climate parameters such as temperature, rainfall, and humidity can be reconstructed by analysing the chemical composition of these growth increments using the presence of stable isotopes and trace elements.

Analyses of the annual — and in some cases, fortnightly, daily and even tidal — increments allow us to reconstruct a detailed timeline of environmental change. This field of study is known as sclerochronology and it has expanded exponentially in the past couple of decades.

The shells, teeth and animal bones that we analyse are the remains of food collected and consumed by people. Therefore climate reconstructions from them can be directly linked to human activity.

We can establish the animal’s season of death and season of exploitation by humans by examining the growth pattern or chemistry of the most recent growth increment. For example, we can use oxygen isotopes to reconstruct the sea surface temperature when the animal died. A very cool temperature tells us that the animal was collected by humans during the winter.

My colleagues and I recently wrote a review article and edited a journal special issue highlighting some of the latest research using these methods. The studies – which included evidence from prehistoric hunter-gatherers in the Mediterranean to historic Inuit sites in Canada – show how people dealt with seasonal variability in the past.

Learning from the past

Climate change is one of the most pressing issues in today’s world.

However, our understanding of how human-induced climate change fits into natural climate variability (pre-industrial) is limited by the instrumental record, which rarely extends beyond a century or so.

Proxy records of past climate variability — such as increments from animal teeth or mollusc shells — extend our understanding of long-term climate variability.

Such abundant archaeological evidence can fill in the gaps from climate records about seasonal and sub-seasonal variation.

We need the robust, quantitative, detailed data we are now getting from archaeological sites around the globe. It helps to contextualise current and future climate change, and to form baselines for environmental monitoring.

Additionally, these climate records are useful for testing and refining global and regional climate models. More accurate climate models give us a better understanding of the overall climate system, and an enhanced ability to predict future climate change.

Such data may help us build resilience to climate change in our modern world.

So next time you tuck into your shellfish dinner, or juicy steak, take a moment to reflect on all of the useful information preserved in the intricate hard parts these creatures leave behind.

Will archaeologists of the future study your discarded shells and bones?

Amy Prendergast, Lecturer in Physical Geography, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.