Anna M. Kotarba-Morley, Flinders University; Alison Crowther, The University of Queensland; Mike W Morley, Flinders University, and Nicole Boivin, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History

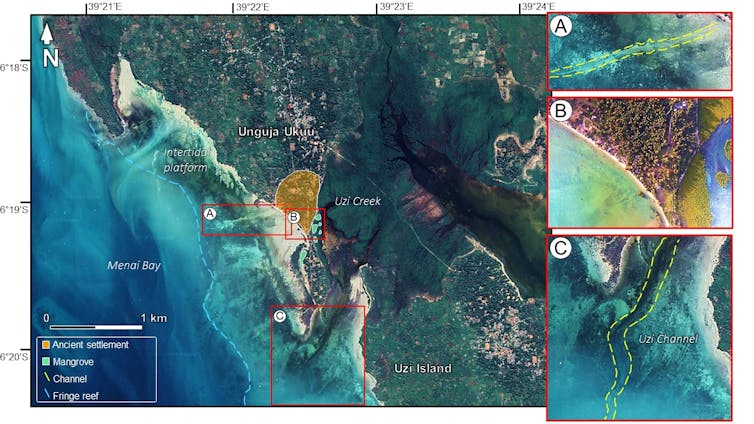

The medieval settlement of Unguja Ukuu, on the Zanzibar Archipelago off the coast of Tanzania, was a key port in an extensive Indian Ocean trade network that linked eastern Africa, southern Arabia, India and Southeast Asia.

Our archaeological research shows how human activities between the seventh and twelfth centuries AD irreversibly modified the shoreline around the site. At first, these changes may have helped the trading settlement develop, but later they may have contributed to its decline and abandonment.

Ancient seafaring

For millennia, the Indian Ocean has been the maritime setting for an early form of globalisation. Large trade networks operated across the vast ocean, foreshadowing modern global shipping networks. Unguja Ukuu was a crucial location in this early trade and an important node in the nascent slave trade out of continental Africa.

Unguja Ukuu was an active settlement from the mid-first millennium until the early second millennium AD. Archaeological evidence and historical accounts suggest Unguja Ukuu is one of the earliest known trading settlements on the Swahili coast.

The rise and fall of trading ports

To understand how and why early ports thrived or declined, it is important to know how the coastal landscape influenced the way traders operated. This includes their choice of mooring locations and their connections to inland locations.

But the question of how these commercial activities in turn modified the coastline has received less attention.

Unguja Ukuu prospered in an ecologically marginal zone, hemmed in between the sandy back-reef shore of Menai Bay and mangrove-banked creeks to the east.

Menai Bay afforded shelter from monsoonal storms and navigable waterways across the shallow inner shelf to the shore. It also provided food and other materials from the mangrove habitat.

This landscape enabled the emergence of the farming, fishing, and trading settlement of Unguja Ukuu.

Sediment, sand and shells

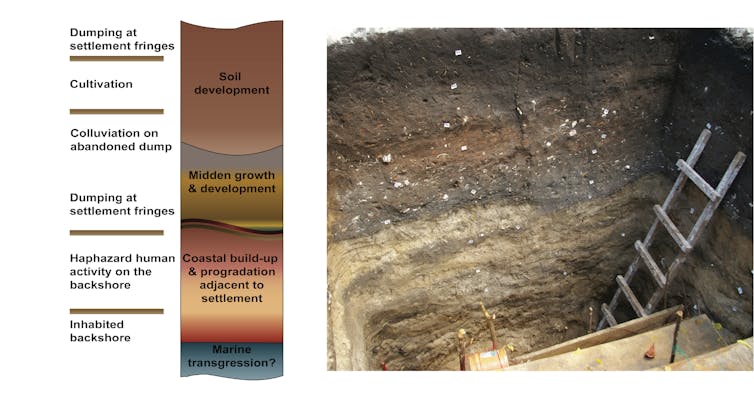

We studied sediments, back-beach sands, and shells at Unguja Ukuu to understand how the settlement had affected its own environment. We found the accumulation of coastal sediments over centuries led to significant changes in the landscape.

Detritus from the settlement, such as food remains, hearths and other domestic waste, helped the beach spread outward into the sea. Our analyses show how human waste and the compaction of ancient surfaces drove the coastline change, supporting the emergence of a major trading site.

As more land was used for urban living and agriculture, more sediment moved from the land to the sea. This contributed to rapid growth of beach fronts, physically altering the coastal landscape and the ecological conditions of the adjacent sea-scape.

These changes in turn could have resulted in habitat shifts and silting of the lagoon which possibly contributed to Unguja Ukuu’s decline.

Early human impacts

Human-made processes might also be implicated in the decline and eventual abandonment of Unguja Ukuu in the second millennium AD. This was an important period in the socio-political and economic transformation of coastal African societies, marking the emergence of maritime Swahili culture.

But suggesting a purely environmental cause for the settlement’s abandonment would be too simplistic. The interaction of coastal villages and harbours with their dynamic landscapes may have had a role in this regional reorganisation of settlements, harbours, and trade flows.

New advances in archaeological science techniques, combined with systematic archaeological analyses, are increasingly allowing us to disentangle natural from human-made drivers of events. Such work often reveals far earlier human impacts than once envisioned, shedding light on the early roots of Earth’s current geological epoch: the Anthropocene, in which human activity is a key force reshaping the planet.

Human-made soil

Our work records snapshots of the evolution of a natural coastal system at the fringes of an early settlement.

River sediments were covered by beach sands containing increasing amounts of human waste accumulating from the mid-seventh century AD. This backshore activity area was used for small-scale subsistence activities (including processing shells for meat), trade, and the dumping of industrial waste.

Earlier urban development shaped Unguja Ukuu’s soils over the long term and through periods of settlement decline and abandonment from the twelfth century AD onwards. A dark earth “anthrosol” (human-made soil) continues to evolve on these archaeological deposits today, supporting cultivation in and around the modern town.

Dark human-made soils such as these, formed by rapid decay of organic- and phosphate-rich waste from the settlement, may be used as markers for as-yet undiscovered archaeological sites on the eastern African coast. Their distinctive dark colour renders the soils easily identifiable on satellite images and other remote-sensing datasets.

Understanding the past to shape the future

Our study clearly shows how human modification of natural environments affected coastal landscapes on an East African island more than 1,000 years ago. These findings are a reminder that humans have been changing our environment for thousands of years – sometimes for the better, and sometimes for the worse.

Studying history and archaeology is not simply about learning from our ancestors’ mistakes so that we don’t repeat them. It is also about ensuring that scientifically rigorous data that show how human activity in the past often altered the landscapes and environments in which people lived is effectively communicated, to both governments and the public.

If we can do this we might be able to make better informed sustainable choices for the future of our planet.

Anna M. Kotarba-Morley, Senior Lecturer in Archaeology, Flinders University; Alison Crowther, Senior Lecture in Archaeology, The University of Queensland; Mike W Morley, Associate Professor, Flinders University, and Nicole Boivin, Director, Department of Archaeology, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.